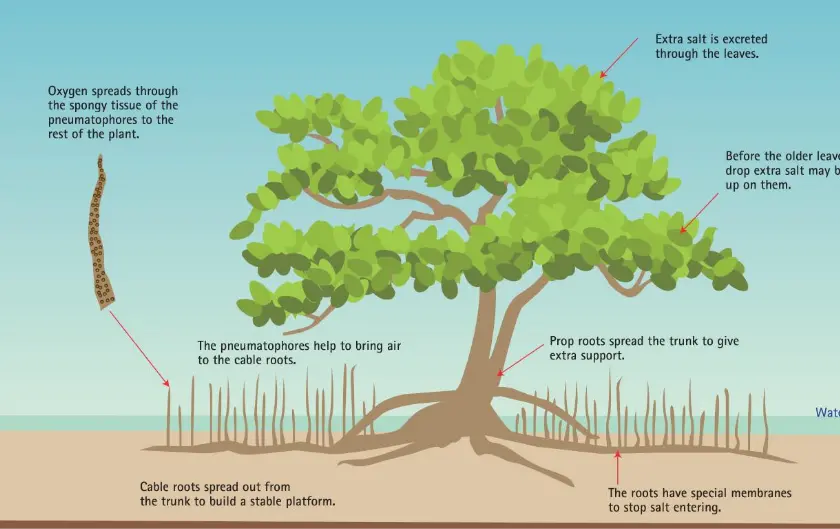

Mangroves are salt-tolerant plants with woody roots that grow in shallow coastal waters. With one “foot” on land and one in the water, these amphibious plants provide food, shelter and nursery habitat for many animals, including birds, crabs, lizards, shrimp, molluscs, snails and fish.

The scientific name for the dominant mangrove species found at KAUST is Avicennia marina, also commonly called grey mangrove or white mangrove because the plant’s leaves and stalks are often colored with salt crystals. A different mangrove species known as Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle), grows in a small area of KAUST near South Beach.

Red Sea mangroves were first described by the Roman natural historian Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE), who wrote, “On the Red Sea, the trees are of a remarkable nature” in reference to their ability to thrive in saltwater. Nine centuries later, the great Arab philosopher and scientist, Abu-Ali al-Husayn Ibn-Sina (980-1037 CE), described the natural history of the Red Sea, including the life cycle of Avicennia marina. Consequently, he was known to the Western world as Avicenna, which explains the scientific name of the plant. In recognition of his contributions to the modern age, a campus building at KAUST now bears his name.

Mangroves are among the most productive ecosystems on Earth. KAUST scientists in the Red Sea Research Center are studying the extent to which these plants benefit the environment — how they sequester, capture and store carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, improve water quality with their tissues and roots, and support other ecosystems, such as coral reefs.

Mangroves are referred to as “blue carbon sinks.” Like terrestrial trees and land plants, they remove CO2 from the atmosphere, yet they bury this carbon at a rate 30 times more than that of boreal, tropical and temperate forests. What makes mangroves different is that they “sink” captured CO2, microalgae, and other dead organic matter trapped by their aerial roots into layers of rich sediment, where carbon is stored, undisturbed, for centuries and even millennia. In this way they help decrease the effects of global warming.

The Health, Safety, and Environment Department sets the operational policies, guidelines and monitoring systems aimed at keeping the mangroves healthy. The health and wellbeing of the KAUST mangrove stands are continuously evaluated using different key performance indicators such as spatial coverage over the years, counts of pneumatophores, crab burrows, gastropods, height, and width of mangrove trees, as well as mangrove sapling density per area.

Thanks to a local conservation efforts, the mangroves at KAUST have increased by over 45 percent from 2005 to 2020. The University now hosts more than 110 hectares (1,100,000 square meters) of mangroves.

Various health and wellbeing monitoring stations are in place throughout KAUST mangrove forest. Detailed data such as counts of crab burrows, pneumatophores, and gastropods have been recorded as the basis of future monitoring for the health of the mangroves.

Various health and wellbeing monitoring stations are in place throughout KAUST mangrove forest. Detailed data such as counts of crab burrows, pneumatophores, and gastropods have been recorded as the basis of future monitoring for the health of the mangroves.

Various health and wellbeing monitoring stations are in place throughout KAUST mangrove forest. Detailed data such as counts of crab burrows, pneumatophores, and gastropods have been recorded as the basis of future monitoring for the health of the mangroves.

Various health and wellbeing monitoring stations are in place throughout KAUST mangrove forest. Detailed data such as counts of crab burrows, pneumatophores, and gastropods have been recorded as the basis of future monitoring for the health of the mangroves.